Leverage as a Software Engineer

A collection of thoughts on creating and owning leverage as a developer.

23rd October 2023

As a software engineer, you are monetizing your knowledge, and your goal is to have unfair advantage against the competition. Who has unfair advantage and who doesn't becomes exceptionally clear in terrible job markets, like the one we are in right now at the time of writing. Generally, there are two ways to have unfair advantage:

- Be knowledgeable in a niche that has low demand but even lower supply

- Be extremely good at something that has high demand and high supply

At LearnWeb3, I deal with these sort of questions almost every day and I've thought about this question a lot. I think point two is harder for most people to achieve, especially those early on their career, so I'll focus on point one in this post.

What is leverage?

Ideally you're in a position where you're not worried about finding a job that meets your minimum criteria - whatever that might be. Perhaps it is a certain amount of money, a focus on a specific field, the ability to work remotely vs in-office, and so on. If you're in this position, you probably have some leverage. It is the ability to do what you want to do, not what you need to do.

It is the difference between getting laid off as part of mass layoffs and then staying unemployed for a year while you grind Leetcode, versus being laid off and then joining another organization within a week that you like.

It is the difference being able to be honest and comfortable with your team and have your voice heard without feeling neglected or ignored, versus being in a toxic environment where you feel like you're not being treated fairly.

It is the difference between between finding it easier to maintain your mental health versus struggling to get through the work day.

This is not to say you should be taking advantage of your leverage and pushing your employer to the limit. You should just be aware of the leverage that you have so you know your capabilities and can make the best decisions for yourself.

Knowledge curves

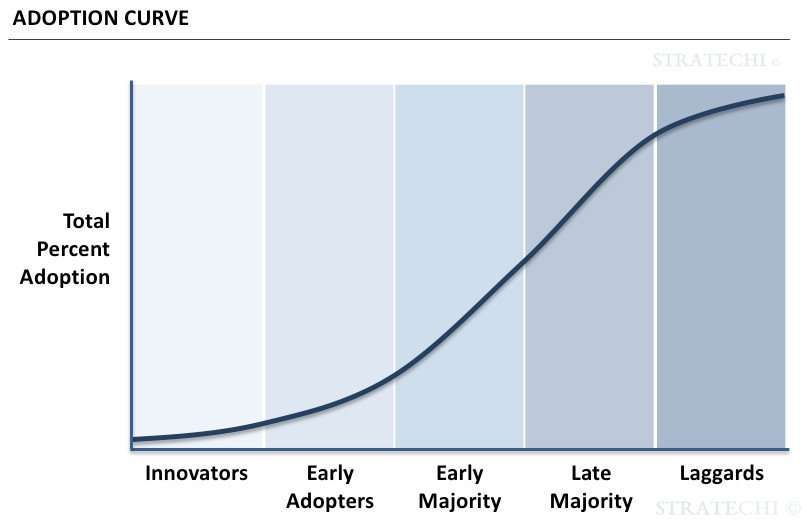

You've probably seen the S shaped adoption curve that is used to describe the adoption of new technologies. It looks something like this:

I believe this curve is also very significant in showing how you can create leverage for yourself and works as a knowledge curve. Depending on your circumstances, you likely choose to learn about a new technology somewhere along this curve. Based on my anecdotal experience, that pattern is fairly consistent in most people and rarely do folks break that pattern without their circumstances having changed.

For example, a "traditional" beginner path is often:

- Get a degree from a college or university

- Learn the most popular technologies - Java, Python, JavaScript, etc.

- Get an entry level job at a company that is hiring

I believe this advice is fairly useless for the most part and only applicable in specific circumstances. If you're someone who isn't particularly focused on their career and only working to pay the bills while you do what you really enjoy, or you're someone who has to pay off significant debt and needs stability in their life, then this advice is probably good for you.

But, if you're someone who can take some amount of risk and has the opportunity to explore, going down this path is not a great way to start off.

Let's take a look at a few examples. In 2023, I think we can say fairly confidently that Rust - the programming language - isn't going anywhere now. Compared to several older established technologies it is still VERY new, but also at a point where we can confidently say that 5 years from now Rust will still be around. Going by the curve above, Rust is somewhere around the second or third section of the graph and growing. There is a certain amount of risk vs. reward ratio that exists with learning, getting good, and building a reputation for yourself within the Rust ecosystem right now.

Now imagine if you were doing that 4-5 years ago, back when Rust was undoubtedly in the "Innovators" stage of the graph. There was a much higher risk but significantly higher upside as well. Very few companies were looking to hire Rust engineers, and the only people working with it were hobbyists with the exception of a couple of organizations who saw its value. If you were one of those people, you would have had a significant amount of leverage in the market as demand for Rust increased. Companies who made the decision to switch over to Rust - for example, Discord - did not have an easy time hiring skilled Rust developers. At that point, it is significantly easier to get your criteria met since you have the advantage of being early within an ecosystem which has low demand but even lower supply.

To be clear, I think there's still value in doing Rust today, just slightly less.

On the flip side, let's look at React. Imagine starting to learn React today for the first time and then using that knowledge to apply to jobs. The competition around you is significantly higher, and you're likely much more easily replaceable - especially if you're a relative beginner in the space. The employer has significantly more leverage than you in this situation and you're likely to have to compromise on your criteria.

This wasn't always true. If you learnt, got good, and built a reputation for yourself within the React ecosystem in it's early days, the potential was massive. But React simply lies on the latter half of the knowledge curve today and is basically expected knowledge of any "Full Stack Developer" job position.

Paul Graham once said that when he was starting Viaweb, he was heavily biased towards hiring engineers who had prior experience with Lisp. Lisp, at the time, was a fairly esoteric language and the only people using it were hobbyists. Graham stated that folks who had done stuff using Lisp were, by nature, more curious, passionate, and had a genuine love for programming instead of just doing it for paying the bills. This seems to be the common factor between those who are willing to experiment with early technology and get good at it, compared to those who are in tech for the supposed glamour.

Identifying early opportunities

Now you might say how do we identify these early opportunities. Honestly, I don't know if there's a set of rules you can follow to do this. It is a combination of luck and timing, but also an immense amount of curiousity and love for the craft. Tech moves fast, and constantly being on top of it is no easy feat. You can subscribe to a hundred newsletters you will never read, or bookmark a thousand tabs you will forget about, and that will not help you out at all.

One thing I've noticed in developers who I think have those tendencies is they often seem contrarian in their beliefs and use platforms in ways the general audience doesn't. A friend of mine once said that Github isn't a version control platform, it's social media. With the feed on Github and the explore tab, you can find so many interesting projects people around the world are working on. You start following them just like you'd follow folks on Twitter, and look at what projects those folks are also following. Very quickly, you can start to see the analogy of Github being a social media platform for developers. I think it was a fascinating way to look at it.

Early + Passion

The most ideal situation you can find yourself in is being early to a technology that you actually are also passionate about. If we remove the passionate part, it is relatively simpler to theorize about what might one day be a massive field. For example, Quantum Computing is a very early stage technology right now that definitely has the potential to change the world - but you must have at least some amount of passion for physics and mathematics to actually be into it.

In crypto I see a lot of people who have been successful at finding this combination, and the amount of leverage they have is very clearly visible.

If you can find that combination for yourself, you are in a very good position.

Switching

One thing I really want to clarify is figuring out when it's time to exit. Imagine a PHP Developer in the early 2010's - the peak of PHP usage across the internet. Yes, I know Wordpress still runs a huge portion of the web - but that is absolutely not reflective of the state of the PHP job market right now. If you were early to PHP, leveraged your way into being highly successful, but then failed to exit that market in favor of the rise of SPA applications and JavaScript, you would have lost a lot of your leverage.

This is equally as hard of a challenge as identifying the right time to enter. Of course, why wouldn't it be? But, just like there are signals for identifying potential in an early stage technology, there are signals for identifying when it's late stage as well. The key one there being identifying great signals in an alternative competitor technology, combined with a lack of innovation in the technology you're currently working with.

The learning paradox

When I come across a student who was told they absolutely MUST learn the MERN stack before anything else and I ask them why they believe it - a lot of the times they claim it's because they were told that's where the most resources are available to learn easily.

I think what is missed, however, in that understanding is the opportunity cost of that decision.

As technology matures, more and more abstractions are created around it. This is a good thing because it allows us to build more complex stuff more easily - but also isn't ideal if your goal is to build a lot of leverage.

Getting to a level where you can call yourself a "Senior React Developer" is significantly harder than calling yourself a "Senior Quantum Computing Engineer", for example.

Yes, it's harder to learn Quantum Computing, but it's also harder for everyone else. Likewise, it's easier to learn React, but it's also easier for everyone else.

I also don't agree that the number of resources should dictate your choice of tech stack to learn. Keeping on with the above example, assuming you have some physical and mathematical background, you can get to a level of decent proficiency with building Quantum Circuits by perhaps going through one book in it's entirety and then building a few projects. I don't think the same can be said about late-stage technologies like React.

The average React developer today knows how to use the framework, but likely has less than 10% the knowledge of how React actually works under the hood. This is why senior-level and higher interviews for React positions often ask about the internal workings of React rather than building frontends using it. In contrast, an engineer who is building in an early-stage ecosystem likely understands a significantly higher % of the internals of the technology they're working with.

Purely in terms of "which content is easier to digest" - yes, the more abstracted one is easier to digest. But, there's also a significantly higher amount of content that you don't know as well because of the high number of abstractions.

Imagine you knew about Rust on day one of Rust's public release and weren't one of the core developers working on the language itself, and a little birdie told you that Rust is going to have a significant impact in the tech world. At that point, there's not a lot of resources you can learn from - which means you spend less time trying to find that perfect Udemy course because there's usually only the primary source that's available to you - and all those abstractions, you get the chance to build those. You build those abstractions, you build a reputation, and you build leverage.

Conclusion

Focus on building leverage, and a lot of your worries will go away. This is much easier said than done.